She goes, It's like when I'm out banging with my goonies.

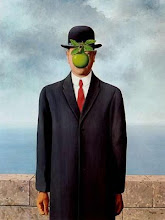

And what Mecca and the rest of Frederick Douglass High are offering is their take on What is flash fiction? For creative inspiration we circle, as a group, Cornelia Parker's suspended sculpture Hanging Fire (Suspected Arson) inside the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston. In journals, we note what we see as well as what we don't see (the arsonist, the people who lived here, the words associated with such a happening). We make character sketches. We interview. We rage and rant, burn and howl.

Go on, Mecca, I say. Tell us more.

It's like when everyone's about to trip, she says.

And? I ask, hoping further details will come together, in the same way the shapes and sizes of this burnt wood somehow do, to represent the delicate blur of imagination and invention —a fiction.

And what? That's my story, fool.

The class buckles under the weight of their terrific laughter.

Unlike me, her peers seem to have a far greater understanding of what Mecca is talking about. They have, I suspect, been witness to this type of scene before. Or worse.

What Mecca is saying is it's about the moment—a flashpoint.

That, and a good old-fashioned gang fight.

Eventually, others let loose with their brave and complicated fictional lives.

***

When I was 11 I wanted to be blind. It seemed this was the missing piece between me and musical greatness. Having spent countless hours on my father's yard sale organ trying to play along with Stevie Wonder records, I was convinced it had to be the glasses. That's why my family would beg me to stop after the first bars of "Higher Ground."

Of course, wearing my older brother's Ray-Bans didn't pan out.

Unfortunately, playing with the lights off proved fruitless as well.

But relying on the same logic that nearly got me electrocuted when I attempted to swim underwater in the ocean with an ordinary flashlight, I took to closing my eyes—all the time. As I figured, maybe living in constant darkness like Stevie was the trick.

Oh, how I was wrong.

And after a tremendous tumble down the stairs, the dream died.

Fast forward to the present. I find myself in a contemporary art museum teaching creative writing to a group of inner-city high school students who, by their own admission, have neither stepped foot inside such a puzzling space nor have even heard the words flash and fiction spoken side by side. If confusion is the face of panic and terror, we are a dead giveaway.

The problem is inspiration. I am unable to show them how to find a story.

It was only after failing to get these frustrated yet willing scribes to set pen to paper that I would put into practice a critical lesson I learned from my attempt to be the next Motown star. And it was something I was already focused on as a fiction writer—the idea of examining the world up close, from each angle, in every light. By feeling my way around our house in those lightless moments, I eventually came to notice what I wasn't seeing.

***

As writer-in-residence at the ICA, my job is to work with Dorchester, Roxbury, and South Boston teenagers on the museum's WallTalk program. Its aim is to create exhibition-inspired narratives (fiction, poetry, drama, personal essay) in response to the art of our time. Audacious? Hopefully. And in the elusive spirit of flash fiction, our hours together in the gallery are terrifying and beautiful and not always fully appreciated at first read. Much like Frederick Douglass High's own twitchy goth specter that is student Shane Daly, who threatens to use a Zippo on his #2 pencil to start his own art project if he doesn't get his chow on, and soon.

Shortly, others begin to voice like-mindedness.

How long does it have to be? they chorus. We don't have all day, yo.

Either hungry or confused or merely restless, it's apparent time is of the essence— literally and narratively. These young authors want what they want and they want it now. It is in this urgency that a flash best operates. If the desire to express the feeling of being alive cannot be afforded a lengthy dramatic arc, the necessity to create a narrative as daring and troubled as a two-minute punk rock song is critical. Think The Ramones' "Blitzkrieg Bop" and you get the picture.

Scribes, I say. By definition flash fiction has to be brief, yet intimate.

How so? Shane asks.

We're in the punch-in-the-gut business, comrade. Offer the reader that feeling in a page or two or three or four and you just might satisfy the nonbeliever.

I point to Parker's installation for evidence.

Why write about a house’s or a church’s history when our story lies in its burning?

Hearing this, Shane pockets his lighter. In a rare show of vulnerability he seizes the opportunity to describe how he had to take his family's rottweiler to the vet to be put down. He reveals the instant the vet stuck the first needle into his beloved Daisy, and how quickly the dog collapsed in his arms.

Didn't take long, did it, I say.

I carried her home in a blanket, he says. I could write about that in less than a page.

Now we're talking, I say.

Suddenly aware of his openness, Shane retreats to the shelter of his leather trench coat.

Let's not forget, I say. This writer brings up a point when he says his story is going to break hearts in under a page. This is attitude. Be defiant. Be daring. Be careful with words.

From across the gallery, Dominic D'Amore shares his thoughts on wasting his time to learn any of this. Into the pages of his Tom Sawyer paperback, he curses.

Well said, Dom, I say. But keep in mind what your man Twain said: The difference between the right word and the almost- right word is the difference between the lightning and the lightning bug.

He shrugs. The others are a hard read as well. Pencils tap; text messages are sent. Sadly, we are at a tragic impasse.

Is this the mystery of flash fiction? I wonder. Is language where we writers part ways? To the rescue, Angela Pierce—my new word for gutsy and wallflower—gutflower.

She peeps, Words kill.

The class erupts in outdoor voices.

Angela, I say. I like how you roll.

***

But maybe it's the way the light surfs across the jagged remains of a suspected arson that holds these young writers' attention, stimulates their imagination. Or maybe it's writing to get to the end if only to stuff your pie hole. Who knows?

In a perfect world I'd like to think the students of Frederick Douglass, like those of us who bother to create anything, are tapped into photographer Walker Evans's plea: Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare. Pry. Listen. Eavesdrop. . . . You are not here long.

Before leaving, we have time to read a story or two. No takers.

Although I expect to hear from Mecca, she points to Tanya Powell, her best friend.

You have to hear this, she says.

What do you say, Tanya? I ask. Want to give it a shot?

She balks, then accepts.

We listen to Tanya describe, in her story "Goodbyes Are for Suckers," the conflicting emotions a teenager experiences just before she forever leaves her family in the Dominican Republic to go to school in Boston, a city she only knows from pictures. What she sees are passengers in their seats, the tarmac outside her window, and so on. What she doesn't see are her family members inside the terminal as well as the home she is leaving and the unexpected feelings that overtake her.

Mecca zones in on me. She winks.

When Tanya finishes with the word ache, I second-guess all my ideas about love.

---

Hanging Fire: A Meta Narrative on Flash Fiction, first appeared in The Grub Street Free Press and was recently reprinted in The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction, ed. Tara Masih